Whether it’s a repeated holiday, yearly lunch, or the lame recurring joke I inflict upon Claire, I reckon tradition offers psychological warmth. Do you have your own conventions that you repeat over and over again?

My rituals unfold like this: the deliberate or accidental start, the adhering — however long it endures — and the anticipation for next time, commencing immediately once the event’s done.

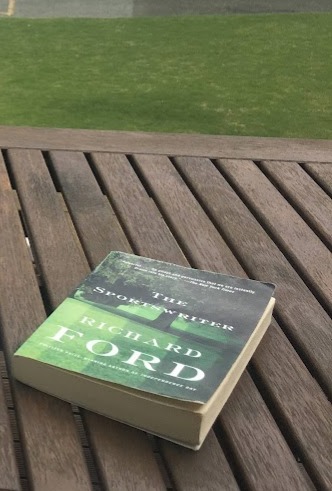

I’ve known Claire since we were thirteen so with much to consider and scribble, head to Port Elliot for a few days to immerse myself. At the beginning of my now biannual writing retreat, I conduct an opening ceremony. This is done by arranging a tableau of items on the townhouse deck’s wooden bench, overlooking Knights Beach. As is our modern way I then take and share a photo, mostly for self-amusement. Like the youngsters.

So, what’s in the photo?

I include my Kapunda Cricket Club hat; the Greg Chappell version (c.1982). It’s my oldest piece of apparel and a life-long companion. It represents youthful frivolity and fellowship. Having been on my head during many summers, I hope it inspires a sunny, grateful tone in my writing. Or at least not a golden duck.

It’s well-worn—perhaps even an heirloom. It’s certainly a talisman from another era—something with personal gravy gravity. Just this week, my eldest, Alex, wore my other beloved cricket cap (Kimba CC) while playing an old, broken-down PE teacher in his Year 12 drama performance. It was a star! Upstaged everyone. So maybe I can pass various cricket items down through the generations. Surely, there are more miserable inheritances. I reckon they’d prefer this to a house.

We can all learn lots from a hat.

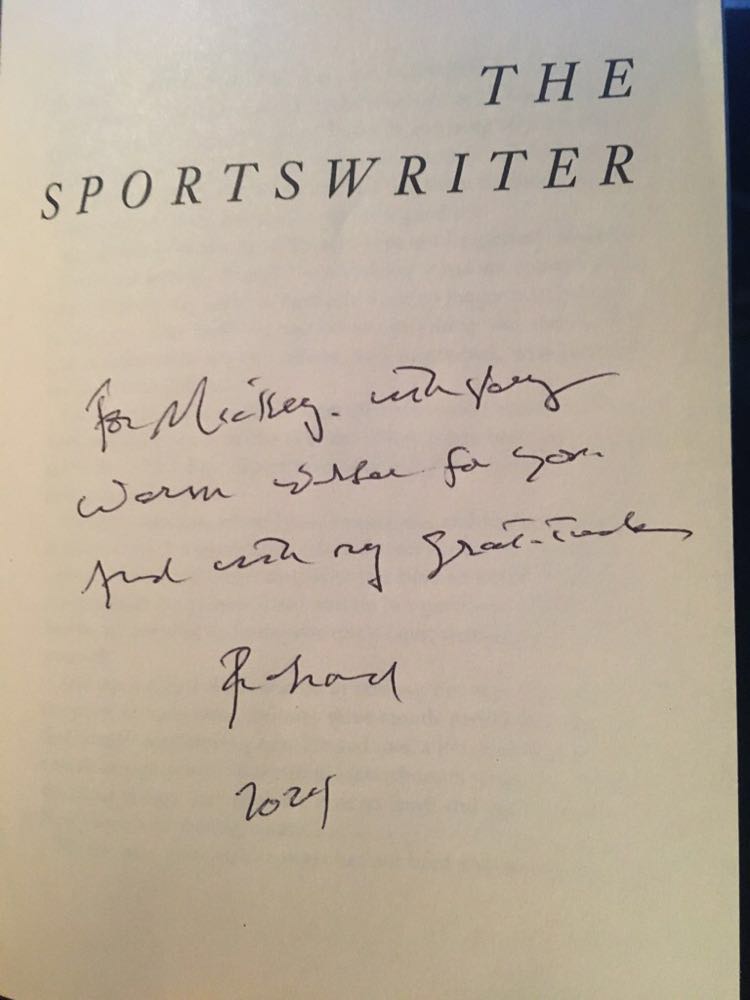

Also in the photo is Richard Ford’s The Sportswriter. Paired with the cricket memorabilia, it suggests a longing for past versions of masculinity—or the shifting seasons of life. The Sportswriter is the first in a series of five stories I’ve read three times across this past decade. It’s about loss, introspection and hope.

As I’m striving for enlightened forms of myself, I want both hat and novel, as personal texts, to be illuminating. To work like flares in the fog.

This writing retreat is for contemplative isolation —not loneliness. I generally seek no company — not even during my late-afternoon pub visits — but see the time as an opportunity to swim in words. Not drowning, waving. My sentences take shape from memory and its attendant considerations. Being beside the glittering, pounding Southern Ocean and adrift in language and reflection is spiritual.

The horizon line on the glass balustrade is enlightening. Did Frank Lloyd Wright once say this? Though it sits near the top third of the photo’s frame, it suggests both elevation and humility—the viewer just above the sea, but not grandly removed from it. I hope this projects gratitude for the occasion and the painterly environment, and encourages the idea that these are combining together, in serene concert.

This tableau proposes that through the laptop and novel, I’m straddling the border between writer and reader. Additionally, I’m fluctuating between labour and leisure and ultimately, thought and the expression of it. My retreat is simultaneously and indistinguishably all of these.

It’s my idea of fun.

Lastly, this is a portrait of myself in retreat— not from life, but toward something. Maybe a particular reckoning with age, or self, or meaning. The animating idea is that we harvest the past to better command our present.