The Rockford Hotel sits midships on Hindley Street. It’s across from the abandoned Rosemount pub, all sticky carpets and blurry memory, another CBD tombstone in the spreading cemetery of inner-city boozers. It’s a mere five-minute amble from Claire’s work, taking us past the contagion of convenience stores, and the sludgy waves of Friday afternoon traffic.

Inside is largely empty and thrillingly quiet. A bar should be either instantly familiar or agreeably alien. We claim some comfy, low chairs, the type popular in motel lobbies. These enhance the theatrical-stage ambiance.

It’s a space of glass and chrome; the kind that makes you feel more important than you actually are — surely the chief function of interior design; to abnormally elevate our self-esteem, if only for the briefest interval. This hermetically sealed allusion is strangely attractive; the air is scrubbed clean, belonging to a space shuttle.

With ale and wine purchased Claire and I submerge into our surrounds. At an adjacent table is a young man — he might be twenty — with calf tattoos and baggy shirt, sitting alone with a beer. He appears as if he belongs in a Macca’s or on a skateboard, click-clacking outside along the darkly stained footpath. I wonder if he’s a rapper, here for a gig at the neighbouring Hindley Street Music Hall. I say to Claire, ‘Is he staying in an upstairs room or like us, just here for a drink?’ We don’t ask him. Hotel bars give people permission to be somebody they prefer.

Pubs necessarily attract punters with no widescreen backstory but those in a venue with rooms attached possess broader narrative possibility. Are they in town for a conference or a nasty meeting? Or maybe clandestine pleasure? Have they just awoken from an ill-advised nap as they adjust from Dallas time?

Our mandatory hot chips appear instantly while despite the sparseness of the bar, Claire’s martini takes nearly twenty minutes to arrive. The staff have no urgency or investment. In that interval, martini aficionado James Bond could dispatch a handful of would-be assassins, take the Aston Martin for a zigzagging spin around Monte Carlo and then seduce his glamorous accomplice.

Then, the dry maraca burst of a martini being shaken clatters across the room. ‘That sounds promising,’ Claire says brightly. I handle the sarcasm in our marriage.

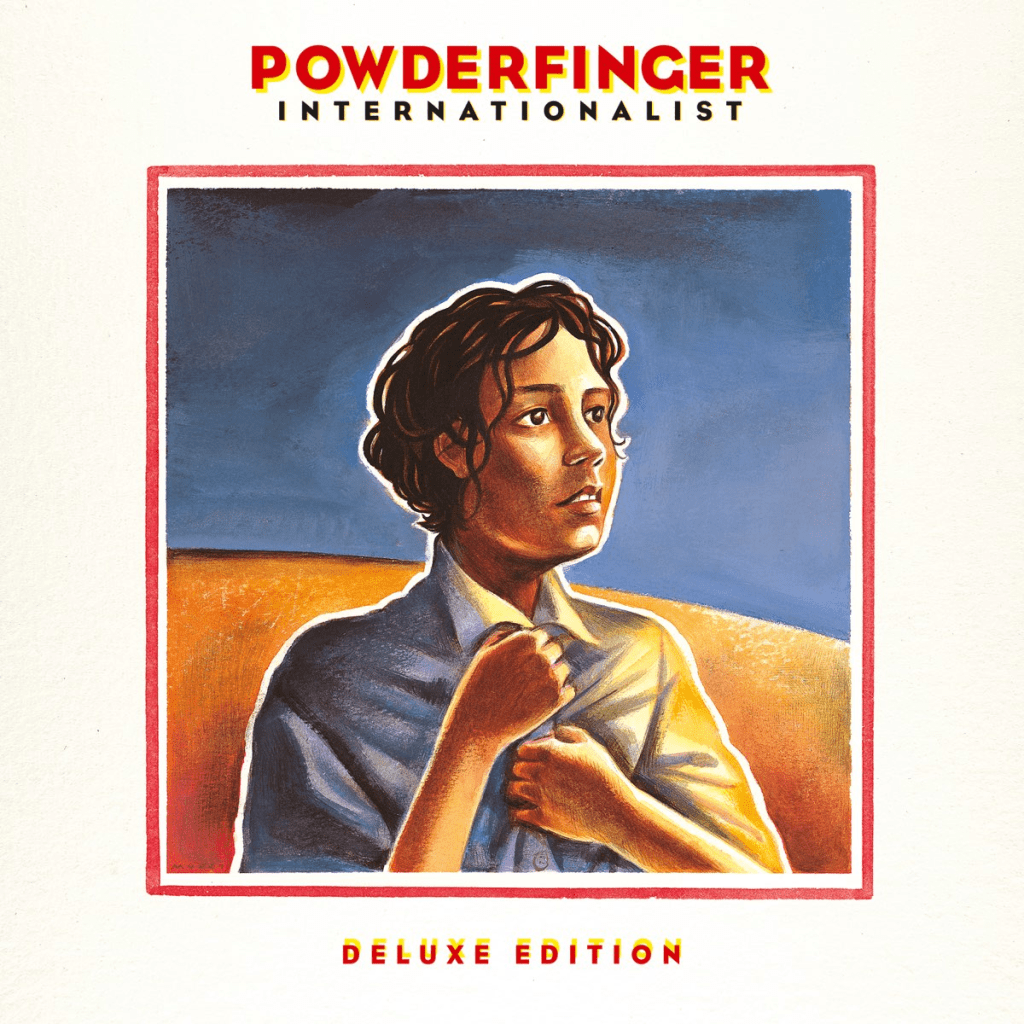

It’d been a restorative escape from the week and into the thoughts of each other, both considered and spontaneous — a shared refuge. Hindley Street is Adelaide’s most scandalous address — Powderfinger even opened The Internationalist with a song named for it. This trodden place keeps remaking itself, and Claire found an untainted nook in which we could fleetingly pause time.