Dearest Alex

A summary of your recent achievements includes your continuing excellence in Drama and, just as impressively, in all of your Year 12 subjects; the inspiring trajectory and resilience you’ve shown in your work at Pasta A Go-Go; and the abundance of positive relationships you cultivate. All wonderful — and of these, I’m truly proud.

But what I want to talk about lies deeper than the visible architecture of these accomplishments. I want to get to the heart of things.

Although capable of admirable assertiveness — you can be feisty on occasion as I well know — there’s a gentleness in you that’s noble and principled. And this connects to kindness, which I believe is the most important quality a person can possess and practise. Here we think of The Dalai Lama, who as the head of Tibetan Buddhism, reminds us that, ‘kindness is my religion.’

The first time I became aware of your gift for kindness — and how others saw it — was in Singapore. Do you remember that boy in your class called Mitt? I don’t think he was enrolled for long but his Mum told me more than once how very compassionate you were to him. You’d included him, looked out for him, and made easier the passage of his young, challenging life. I don’t know how any of this came to be but it gladdened me that your role in this appeared to be voluntary and offered unconditionally. I was delighted, and moved, to be the Dad of someone kind. I still am. Wherever they are, I expect his family still remembers you warmly.

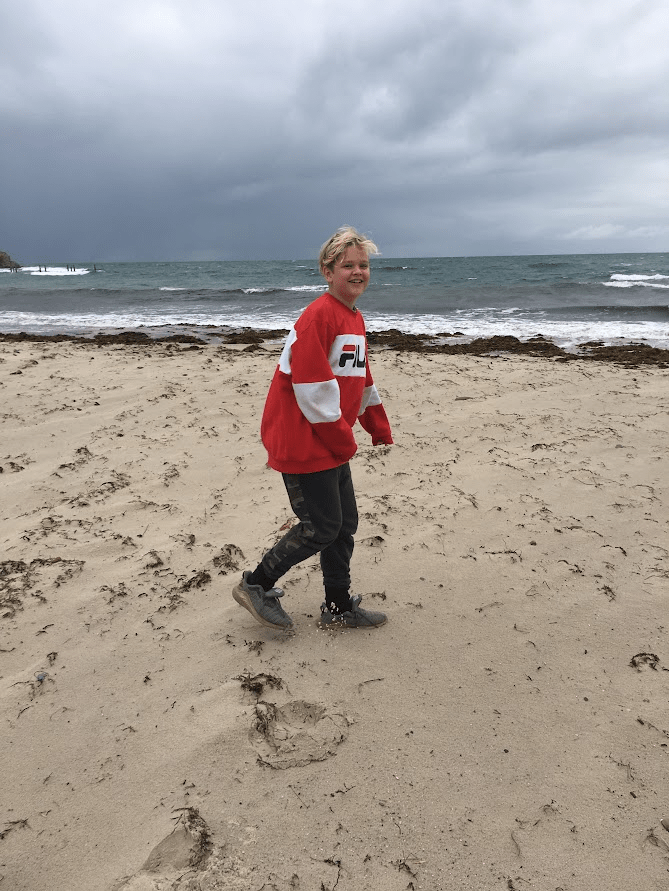

I also admire your appetite for experiences and your receptiveness towards possibility. For me, a chief joy in going somewhere with you and Max is in witnessing your engagement and the subsequent meaning you then collect from travelling. Agreeably curious, you’re inclined towards an open-hearted life.

This was especially evident in Sydney on our coastal walk from Bondi to Coogee. Striding along, chatting with your brother, taking in that rugged sprawl of ocean and sky, clicking some photos — I loved being both a participant and witness to it. And how you do so in a good-natured way is, I hope, a predictor of a happy and fulfilling life.

Another favourite memory: the Lake Lap. I loved how quickly you turned our late afternoon drives around Lake Bonney into a ritual — and how you not only relished the anticipation and the loop itself, but also the talk that followed. You’ve always had the rare ability to find joy and connection in life’s simple rhythms.

Being a dad involves a lot of watching — scanning for all kinds of clues. Happily, in you, I’ve mostly seen encouraging ones.

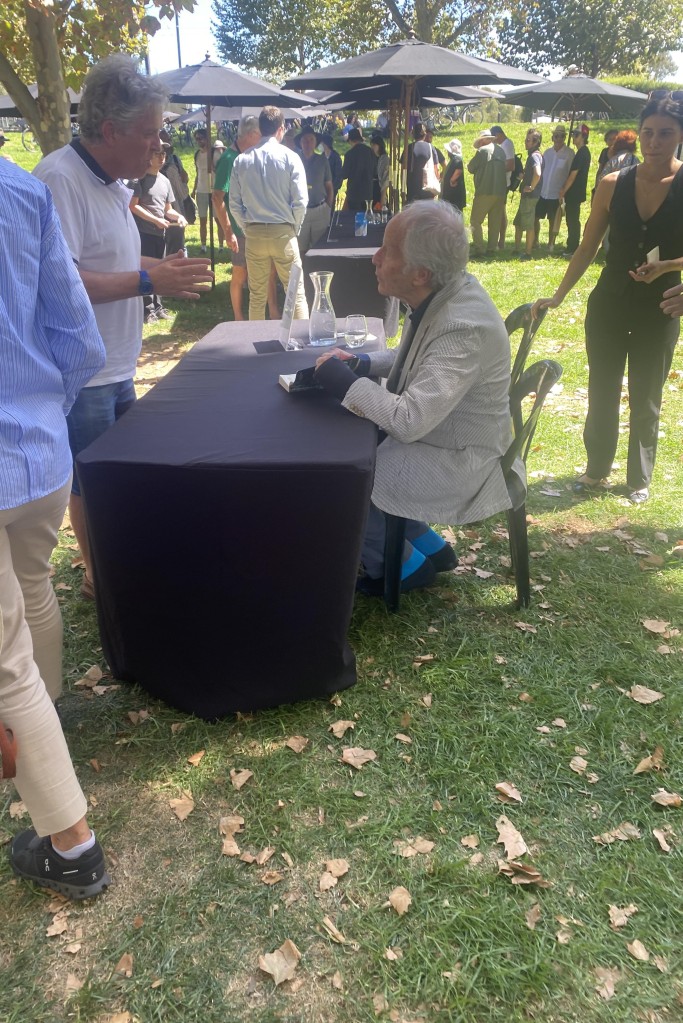

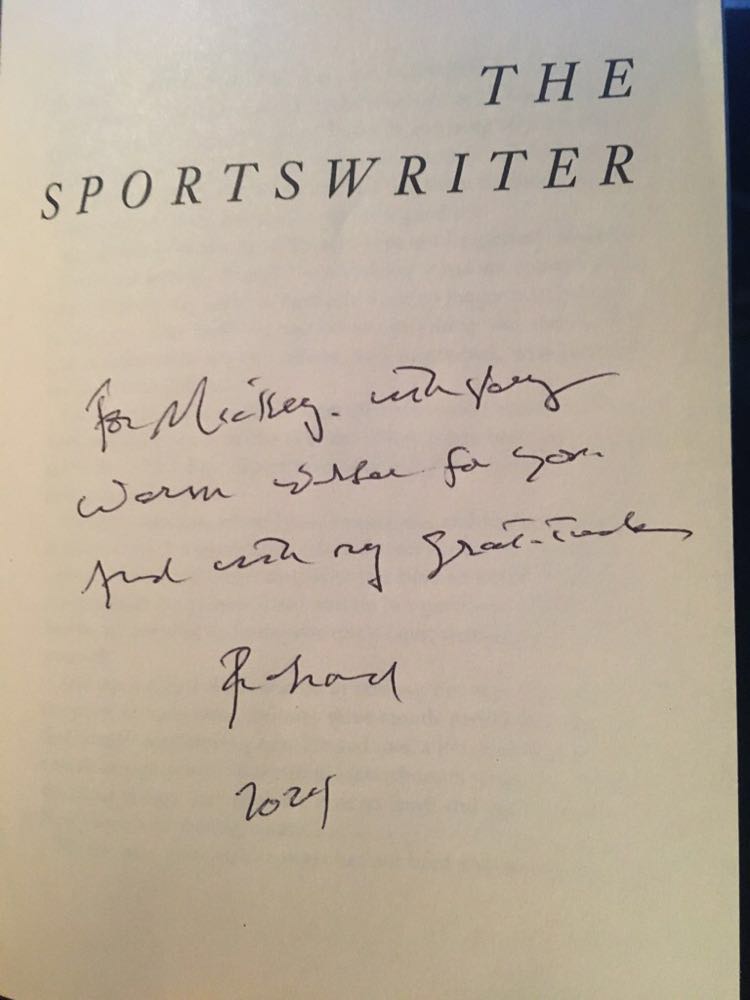

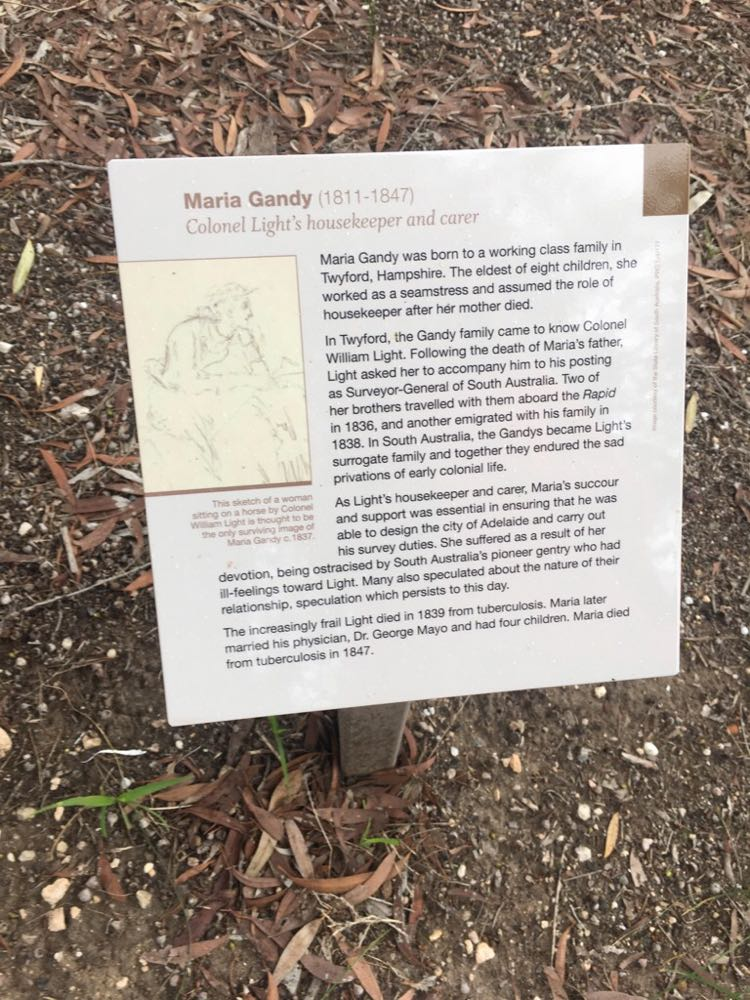

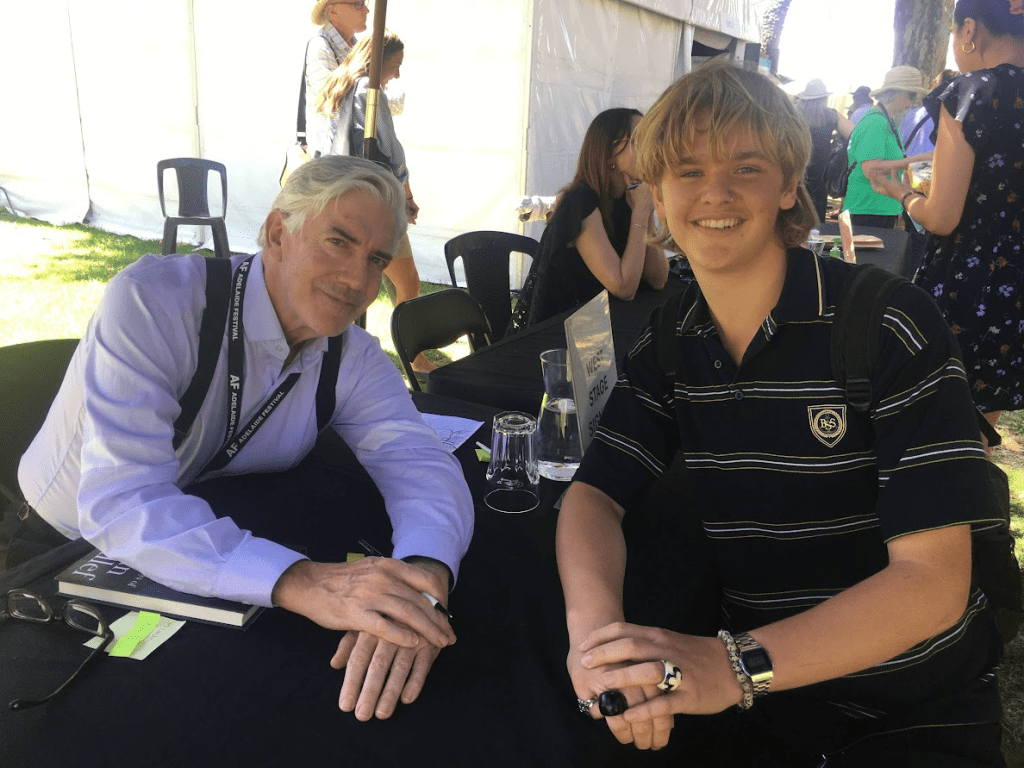

Last March, I made you a spontaneous offer: let’s go to Adelaide Writers’ Week to hear my favourite writer, Richard Ford, and then drive down to Moana — swim, eat at a café, and later, back in our cabin, watch a Bond film. Of course, you accepted with your usual, wholehearted enthusiasm. You bought into this with immediate unreservedness and listened to the literary discussion with patience and real interest. This passage from The Sportswriter — one of Ford’s best — speaks to perspective, hopefulness, and curiosity

I read somewhere it is psychologically beneficial to stand near things greater and more powerful than you yourself, so as to dwarf yourself (and your piddlyass bothers) by comparison. To do so, the writer said, released the spirit from its everyday moorings, and accounted for why Montanans and Sherpas, who live near daunting mountains, aren’t much at complaining or nettlesome introspection. He was writing about better “uses” to be made of skyscrapers, and if you ask me the guy was right on the money. All alone now beside the humming train cars, I actually do feel my moorings slacken, and I will say it again, perhaps for the last time: there is mystery everywhere, even in a vulgar, urine-scented, suburban depot such as this. You have only to let yourself in for it. You can never know what’s coming next. Always there is the chance it will be — miraculous to say — something you want.

I was delighted — you’ve always been someone who brings me frequent delight — when unprovoked, you announced that you’d like to go to this year’s Adelaide Writers’ Week to hear one of our idols: Shaun Micallef. I was impressed that you’d investigated the programme and this showed a healthy disposition towards a cultured life and learning. It also showed me that your curiosity now moves under its own steam.

For a number of seasons watching Mad As Hell on Wednesday nights was our ritual. I loved how ready you were to laugh at it and appreciate its absurd satire. It was tremendous fun and I was thrilled by your quick sense of humour — a necessity as well as a reliable forecaster of future success. We’d roar at Sir Bobo Gargle (release the Kraken!), gasp at Draymella Burt, and laugh at the cigar-chomping Darius Horsham who’d always finish with, ‘Don’t be an economic girly-man.’ There was a quiet magic and symmetry in us meeting and obtaining autographs from both Ford and Micallef. I hope you and I can continue to attend Adelaide Writers’ Week.

This letter is also meant to reflect on ambition and integrity — and I know you have an abundance of both. They’ll serve you well in this life which needs them. I remember your first day at school in Singapore — the morning heat rising, the skyscrapers shimmering — when you climbed aboard that little bus bound for Orchard Road and the great unknown. Your journey had begun.

These brief years have vanished, your final school day looms, and you’re about to go into the world. In my quiet moments, I used to wonder about the future and how you would look, sound, and be as an adult. Now, suddenly, that future is here. You stand at its edge — optimistic, imaginative, kind. I know you’ll be all types of magnificent.

Off you go.

Love always,

Dad