The premise of Independence Day, Richard Ford’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, is simple. Frank Bascombe takes his sixteen-year-old son Paul on a road trip to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, which ends badly. In Be Mine, the final instalment of the series, the narrator and his dying middle-aged son embark upon a last road trip, this time to Mt. Rushmore.

My son Alex and I are going on a short road trip to Moana, but our first stop is Writers’ Week as I want him to again witness the merits of a life with conversations and stories. He’s largely agreeable so with little persuasive effort, we’re here to listen to Richard Ford speak about his writing and probably, the characters of Frank and Paul.

While that’s fiction and our experiences are (aspirationally) real, the parallels seem both captivating and unsettling. The thought comes to me again: I’ve delayed a road trip with my sixteen-year-old son to hear a novelist enlarge upon a father and son on two heart-breaking road trips. I trust I’m not tempting any type of cosmic irony to drape its wicked self over this bonding weekend away.

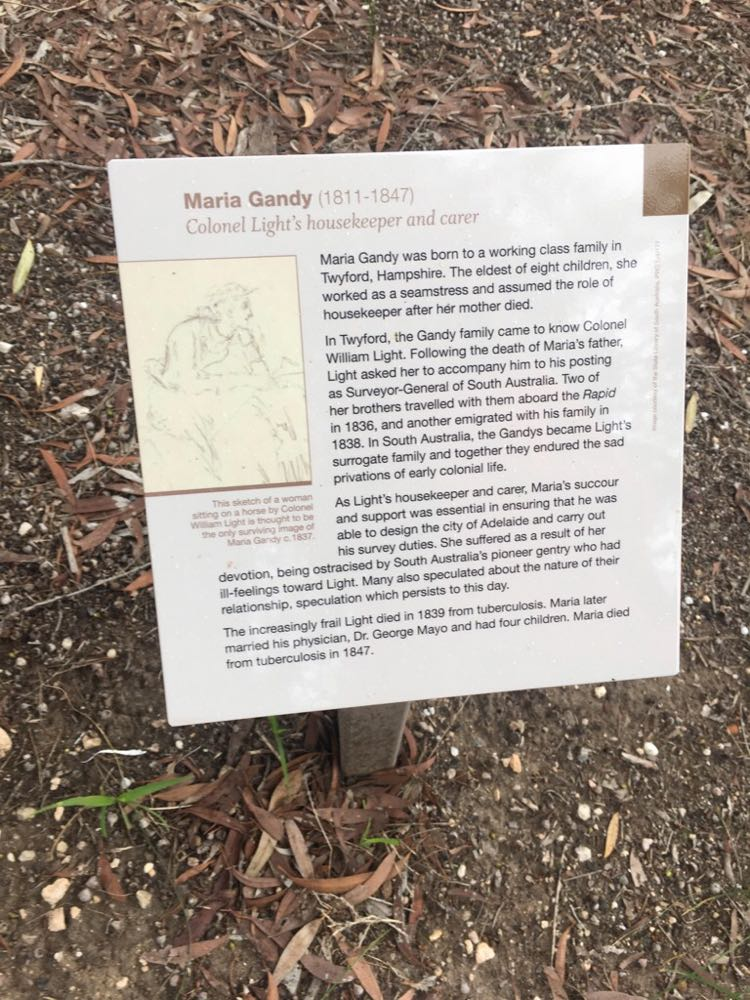

Lunchtime underneath the canopy in the Pioneer Women’s Memorial Garden. That Alex is here with an open mind and open heart, and willing to indulge his dad strikes me as a scarce act of teenaged generosity. I vow to afterwards buy him a coke for the drive. I spot the Footy Almanac’s editor-in-chief Harmsy and we’ve a quick chat.

Richard Ford is interviewed for about forty minutes, and it’s engrossing. Profoundly considered and droll and pleasingly, approaching stern when provoked, he makes references to Virginia Woolf (he’s a fan) and Samuel Beckett (he’s not a fan). I record the discussion on my phone, and Claire (elsewhere unavoidably) and I will listen to it one night soon over a Shiraz as if it’s an unedited podcast.

I rarely carry my backpack but do today just in case there’s a book signing and in it’s my beloved copy of The Sportswriter. I’ve not anticipated an autograph since Joel Garner at an Angaston Oval cricket clinic in 1975. He was the biggest human I (or likely the Barossa) had ever seen. Following our applause, the interviewer invites us to form a queue.

Rushing politely, I find myself about a dozen deep in the line. Alex stands with me. He’s a Beatles fan (for which I’m also thankful) and I say, ‘You know that chatting with this writer will be my meeting McCartney moment?’ He nods.

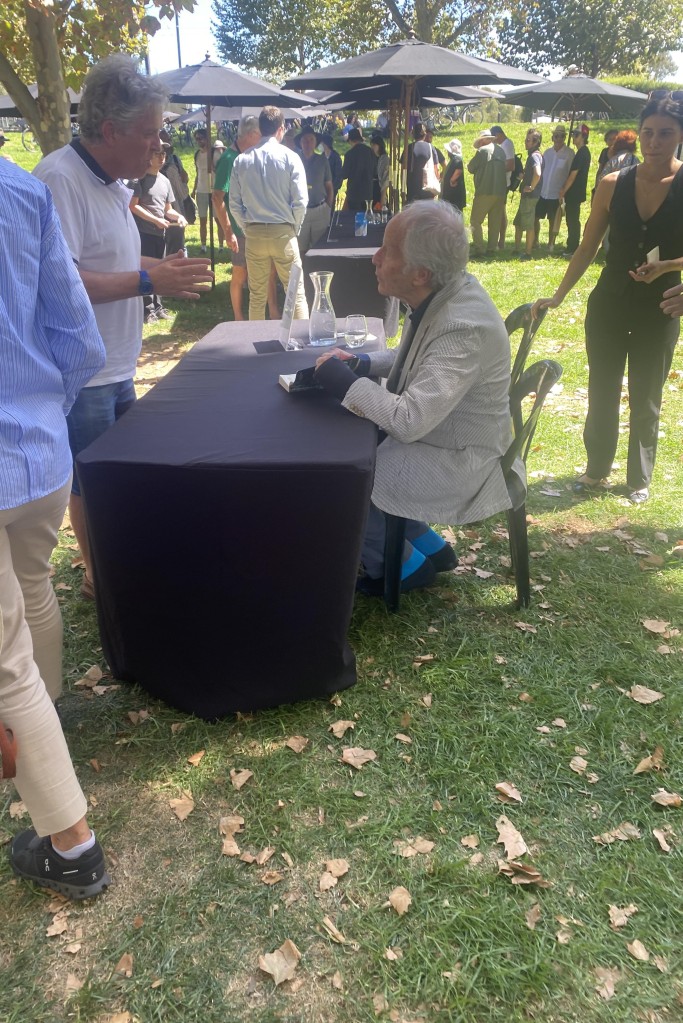

Introducing ourselves, we shake hands. He’s sitting at a table. Eighty-years-old and greyhound fit, Ford has hypnotically blue eyes (matching his socks) reminiscent of the late Bond but alive actor, Daniel Craig. I’ve hazily rehearsed what I say, and the opportunity doesn’t get to me as I imagined it might.

I begin, ‘I’ve read all the Bascombe novels three times except for the last. But I will. They’ve made such a huge impact upon me, and I’ve happily accepted that I’ll pretty much re-read them constantly from here on in.’

Desperately gushing? Probably.

Richard (we’ve progressed to first names) replies with an affirming chortle, ‘Well, some books can hang around.’

I tell him the story of a Saturday night last autumn just prior to the publication of his final Bascombe novel. I explain, ‘I’d read a preview of the book and was telling my wife Claire about it over a Shiraz (now a theme, I know). And I mentioned the central tragedy of the father and son relationship and the son dying. I then realised that all this represented a loss for me too as a reader, so I shed a few tears.’

Richard continued peering at me fixedly with what I imagine’s a blend of deeply practised writerly attention and unshakeable southern manners. Acknowledging my revelations, he nods.

I’m now in full Sunday confessional mode, for I need this man to know how important his creations are to me. Perhaps I’m epiphanic, emblematically at large in New Jersey, like Frank Bascombe himself. ‘It’s the only time I’ve cried at a book before I’ve read it, such is the power of your storytelling, and the remarkable insights. Thank you for this.’

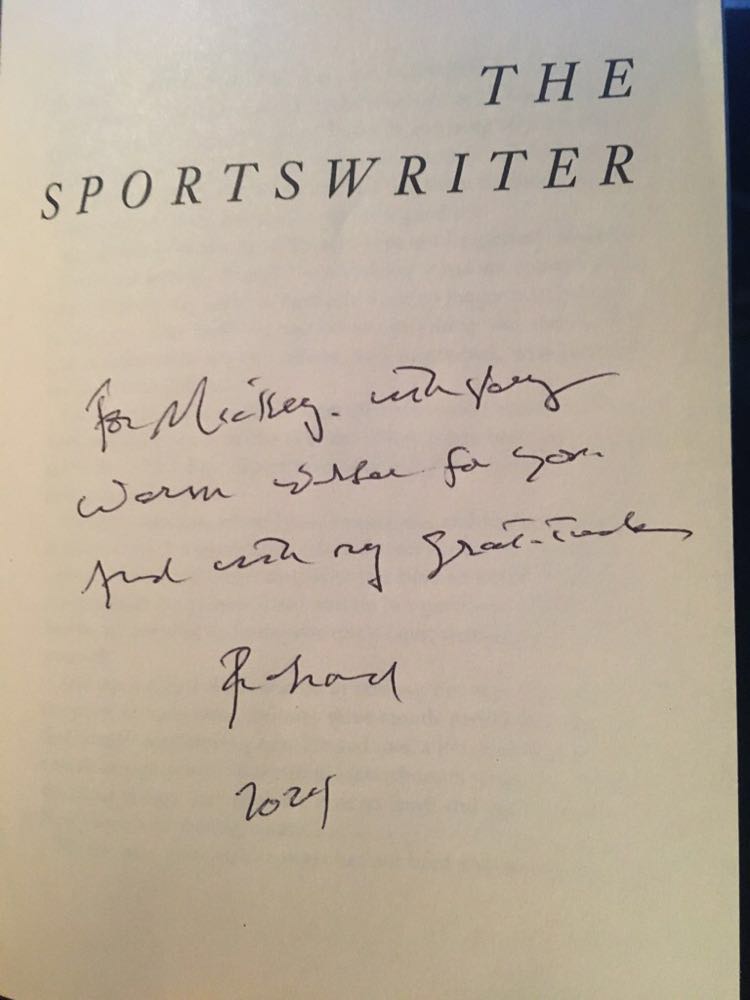

As he signs the title page, I feel a sense of gifted camaraderie. The waiting line is lengthy, and so I conclude, ‘I’m urging my wife to read your books when we retire. I talk about them so much.’

Richard laughs, ‘You’ll hand her a list!’

I also cackle, ‘I think so.’

He thanks me for coming and again we shake hands. The adage cautions against meeting your heroes but encountering this literary giant has been joyous. Alex and I stroll through the garden’s dappled light and up sundrenched King William Street.